gooood团队采访世界各地的有趣创意人,欢迎您的推荐和建议。第27期为您奉上的是联合国教科文组织“土制建筑、建筑文化与可持续发展”的首席及荣誉教授,Studio Anna Heringer 创始人 Anna Heringer。更多关于她,请至:Studio Anna Heringer on gooood

gooood team interviews creative from all over the world. Your recommendations and suggestions are welcomed! gooood Interview NO.27 introduces architect Anna Heringer, founder of Studio Anna Heringer and honorary professor of the UNESCO Chair of Earthen Architecture, Building Cultures, and Sustainable Development. More:Studio Anna Heringer on gooood

出品人:向玲 Producer: Xiang Ling

特邀编辑 | 采访、撰稿:程宁馨 Interview/Text: Cheng Ningxin,编辑:李东颖 Editor: Sara Li

网站排版编辑:陈诺嘉 Website layout and editor: Chen Nuojia

大数据时代狂奔而来,然而建筑行业迟迟没有被渗透。因此有人为建筑的未来而焦虑;有人问,建筑是否已经是最后的人文主义学科?以人类为本位不是劣势,它恰巧是属于建筑的能动性的切入口。让我们和建筑大师们聊聊天,从设计背后鲜为人知的故事展开,去认识一个地方、了解一群人、⻅识一种生活。透过建筑师的经历和⻅解,剖析我们行业的社会价值和能动性。

The Big Data revolution is updating one industry after another, but architecture is hard to be related to data. Architecture is fundamentally rooted in humans and humans’ life. Then, how does our discipline claim its relevance in today’s age? This anxiety about the architectural career and the discipline comes from an incomplete understanding of the role of architects and the power of architecture. Responding to the confusion of the agency of architecture and architects, conversations with the unconventional architects will tell stories of the architects’ role and the life of people involved in the projects.

Interview

gooood x Anna Heringer

Anna Heringer来自奥地利和巴伐利亚交界处的小镇劳芬。在19岁的时候,她旅居孟加拉一年,跟随非政府组织Dipshikha学习可持续发展。对于Anna Heringer来说,建筑是改善生活的工具。作为一名建筑师,以及联合国教科文组织“土制建筑、建筑文化与可持续发展”的首席、荣誉教授,她专注于使用自然的建筑材料。Anna Heringer从1997年起就开始积极参与孟加拉的合作发展。她与Eike Roswag合作的代表作METI学校在2005年建成,并在2007年获得阿卡汗建筑奖。迄今为止,Anna Heringer的建成作品遍及亚洲、非洲、欧洲。与此同时,她也在包括苏黎世联邦理工学院、慕尼黑工业大学、马德里理工大学、哈佛设计学院教授她和Martin Rauch共同开发的“Clay Storming”工艺。

Anna Heringer屡获奖项:全球可持续建筑奖(2016)、AR新兴建筑奖(2018)、哈佛设计学院 LoebFellowship、RIBA International Fellowship。她的作品在纽约现代艺术博物馆(MoMA)、伦敦V&A博物馆、威尼斯双年展等处发表展出。2017年,Anna Heringer在TED大会演讲。(点击这里查看TED演讲)

Anna Heringer grew up in Laufen, a small town at the Austrian-Bavarian border. At the age of 19 she lived in Bangladesh for almost a year, where she had the chance to learn from the NGO Dipshikha about sustainable development work. For Anna Heringer architecture is a tool to improve lives. As an architect and honorary professor of the UNESCO Chair of Earthen Architecture, Building Cultures, and Sustainable Development, she is focusing on the use of natural building materials. She has been actively involved in development cooperation in Bangladesh since 1997. Her diploma work, the METI School in Rudrapur was realized in 2005 in collaboration with Eike Roswag and won the Aga Khan Award for Architecture in 2007. Over the years, Anna has realized further projects in Asia, Africa, and Europe. Together with Martin Rauch she has developed the method of Clay Storming that she teaches at various universities, including ETH Zurich, UP Madrid, TU Munich and GSD/Harvard.

She received numerous honors: the Global Award for Sustainable Architecture, the AR Emerging Architecture Awards in 2006 and 2008, the Loeb Fellowship at Harvard’s GSD and a RIBA International Fellowship. Her work was widely published and exhibited in the MoMA New York, the V&A Museum in London and at the Venice Biennale among other places. In 2017 she was invited to give a TED talk. (click HERE to listen to the TED talk)

▼Anna Heringer

_____________

工作室与孟加拉

Studio and Bangladesh

“每个地方都有独特的自然资源,当地人有自己的特长。如果可以运用好这些资源,你最终能创造出真切而有力的设计。”

“Every place has natural resources and people have specific talents. If you create architecture out of these potentials, you will ultimately create something very authentic and strong.”

在我们的工作室里,我们争取只做会给大家带来积极影响的、有意义的项目。这些项目是我们从道义、生态等各个角度上都认同的。尽管这一点对工作室的资金运营有很大的挑战,但是我们从2005年坚持到了今天。能从一件对你有意义的事情中找到谋生立足的方式,这会让你坚定对自己的信心。

At our studio, we try to only do projects that bring meaning and have a positive impact on others, and the projects that we fully believe in are ethical, ecological and touch all other aspects. This can be financially challenging, but we have carried it out from 2005 until now. It gives confidence when you can do what’s meaningful to you and find the means to survive financially.

▼Anna Heringer在工作室工作,Anna Heringer at her studio ©Alizée Cugney

我第一次接触孟加拉是在学建筑之前,当时在非盈利组织Dipshikha的组织下做志愿者。我想了解当地农村发展,尤其是与自然和谐共生之道。当地人生活简单,寡欲自足。他们自己创造生产生活所需。我惊诧于这些简朴的当地人自己创造出来的生活中所蕴含的充实与美好。我从志愿者工作的组织学到,因地制宜、自给自足、不依赖外界才是可持续发展的最有效途径。这就是我在之后的建筑中所追求的。

I went to Bangladesh with a volunteer organization before I started studying architecture. I wanted to learn rural development and how to live in harmony with nature. The people there live a simple life with little needs. I was impressed by the abundance, the richness and the beauty of the things the locals created for their daily life. I learned from my host organization that the most effective strategy in sustainable development is to use the existing resources and be independent of external support. This is what I try to do with my architecture later on.

▼孟加拉村庄中的简单生活,the simple life in Bangladesh Village ©Studio Anna Heringer

我觉得要从更广义的角度来看就地取材这个问题。每个人都有自己的潜能和财富。如果你能挖掘自己的潜能,人尽其才,物尽其用,就能自食其力。如果你嫉妒、模仿别人走的路,就永远不能自力更生。设计也是一样的道理。每个地方都有独特的自然资源,当地人有自己的特长。如果可以运用好这些资源,你最终能创造出真切而有力的设计。

I think keeping the construction and material procurement in the local area is a general thing. Everyone has potential. If you develop these (existing) resources and value these resources, then you are standing more on your own feet. If you copy and are jealous of what others do, you’ll never stand on stable feet. It’s the same thing for architecture. Every place has natural resources and people have specific talents. If you create architecture out of these potentials, you will ultimately create something very authentic and strong.

▼植根于自然的乡村生活,village life rooted in nature ©Studio Anna Heringer

_______________

在孟加拉的建筑实践

Architectural practices in Bangladesh

“当你身在建造的过程中的时候,就能体会到其中的力量。这个过程不仅能营造一个建筑物,更能构建一个社区。”

“When you live on the construction site with the people and become part of this process, you can understand its power. We can use this process to build more than a building, but a community.”

1.

请介绍一下METI学校项目的背景。

Could you please introduce the background of the METI School?

我十九岁第一次到Rudrapur的时候,感到那里的一切都很宁静。我能感觉自己走的比往常慢,所有的感官都苏醒了,没有了交通的噪音,能听到鸟叫声、昆虫声、人们的歌声……一切都很浓烈,但同时又很柔和。当地人的织物色彩艳丽,纱丽是浓郁的绿色。村子里会有一些紧凑的巷子,但是由于村子里的茅草屋是由村民的双手搭建的,当你身处其中时,不会感到有任何扎眼的景象——有一种柔和镶嵌在其中。

I was 19 when I first arrived at Rudrapur in Bangladesh. I felt everything calmed down. I walked slower than usual. My senses were awakened: away from the city noise, I could hear the birds, the insects, people singing… Everything was intense, and at the same time, so soft. The local fabrics are colorful, such as rich green saris. The villages can have dense alleys, but you would not feel anything is harsh when you are in a village made of thatch shaped by hand – there’s a kind of softness embedded.

▼位于孟加拉北部的村子Rudrapur,Rudrapur, a village in northern Bangladesh ©Studio Anna Heringer

▼孟加拉当地的茅草房,thatched houses in Bangladesh ©Studio Anna Heringer

不可否认当地也是贫穷的。但是我认为,与大自然的和谐相处带来了一种和土地之间的信任。这是在城市中很难感受到的。

Of course, there is also poverty. But I think the feeling of being in harmony with nature raises a sense of trust as you are part of nature. This is what you can hardly feel when living in cities.

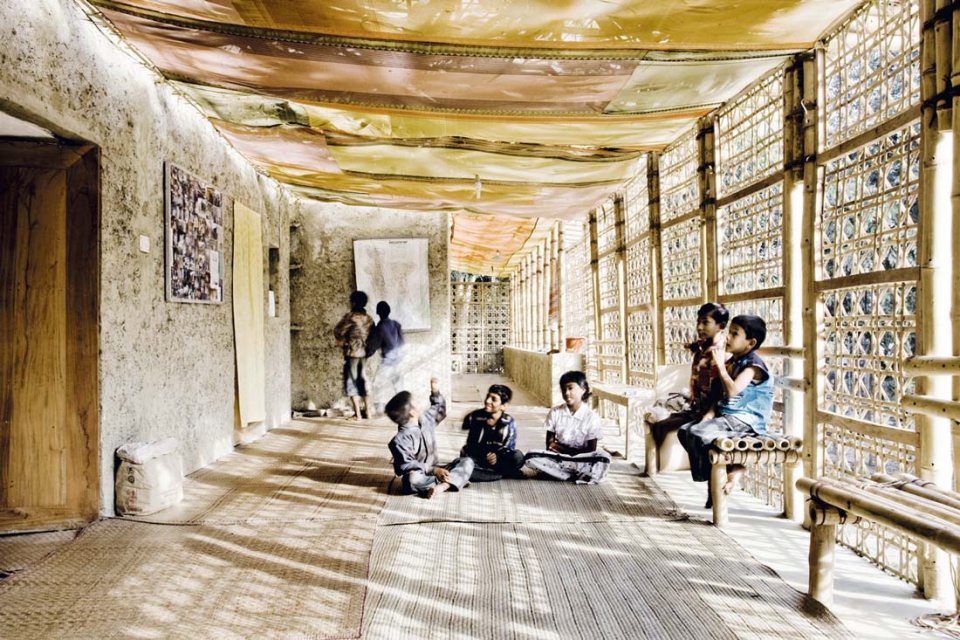

▼METI学校(点击这里查看更多),METI School (click HERE to view more) ©Kurt Hoerbst

▼METI学校施工过程,METI School in construction ©Kurt Hoerbst

2.

您不仅设计了学校的建筑,还设计了一整套的建造过程,让村民参与其中。您从设计建筑到设计系统的转变,是什么时候如何发生的?

In this particular project, you designed the construction process to engage more local villagers. At what moment did it occur to you that you want to expand the design from the building to the whole system it relates to?

一直以来我们都在学如何设计建筑,但从没有去学要如何设计建造过程。但是当你身在建造的过程中的时候,就能体会到其中的力量。这个过程不仅能营造一个建筑物,更能构建一个社区。当你领会到这一点,就会很自然地更有意地把这种力量运用在下一个设计中。我在第一次设计时,村里的男人们告诉我,妇女参与施工不符合当地的习俗,我并没有能够让妇女们参与到项目的建造。在进行第二个项目的时候,碰巧有个意外的事件。当时我带了一群学生到村子里,其中有不少漂亮的女学生。男人们常常和学生们眉来眼去的,于是妻子们有些吃醋。我看出了她们的紧张,跟她们交谈,了解了状况之后,我们一起讨论了工地上有哪些她们可以参与的任务。妻子一般在家里承担涂漆的工作,所以我调整了一下涂料相关的设计,改成她们可以徒手完成的。她们嘱咐我不要让丈夫们知道。第二天的时候,她们像往常一样做着早上的日常。五分钟后,她们突然出现在工地上。丈夫们来到的时候,一开始都很失望地拉长着脸。一个星期之后,他们开始跟自己的妻子眉来眼去的。这样一来,工地上的气氛就欢快了起来。没有多花一分钱,就让他们建立起了团队,还改善了他们之间的关系。

We always learn how to design a building, but we never learn how to design the process. However, when you live on the construction site with the people and become part of this process, you can understand its power. We can use this process to build more than a building, but a community. Once I experienced that, I naturally use the power of that process more intentionally than I did previously. For example, I did not involve the women in the first project, the METI School, as the locals told me it is not in their tradition for women to work on construction sites. Then, it so happened that I had some beautiful students with me working on the next project (DESI Training Center), and the wives got jealous as their husbands were flirting with the students. They looked stressed to me. I talked to them and understood the situation; then, we came about discussing what type of work the women could do and figured out a plan for them to work on the job site. The women usually do the plastering of their houses, so I decided to change the way we planned to plaster the building so that the women could do it by hand. The women asked me not to tell their husbands that they are joining the construction. The next day, the women did their home morning routine as usual,then showed up on the site five minutes later. When the husbands arrived at the construction site, of course, they were a bit disappointed that the women were also there. But after a week, they started flirting with their own wives. Then we had an open atmosphere and a joyful situation on the site. For the same amount of money, they worked as a team and improved their relationships.

▼让当地妇女参与到建设中,将墙涂成红色,local women participated in the construction, plastering the wall into red © DESI construction team

3.

在DESI学校中,设计系统对建筑设计有何影响?

In DESI Training Center, how did the design of the system influence the architectural design?

我一开始并没有想把DESI学校涂成红色,最初的计划是让建筑的外立面像METI学校一样保持最自然原始的状态。但是我想既然我们想把涂漆融入设计,那就用热烈的红色。而且要用手来涂而不是用抹子,这样没有笔直的线条,墙面就会有柔和的触感。

For example, I was not planning to plaster the DESI Training Center in red at all. I was thinking of having it raw, as the METI school. As I thought, okay, we need some plastering, why not use the brilliant red? If you make it by hand rather than with the trowels, the edges might not be as straight, but it has a softer touch when it’s done by hand.

▼DESI学校立面,部分被涂成红色(点击这里查看更多),DESI Training Center, part was plastered red (click HERE to view more) ©Kurt Hoerbst

▼DESI学校室内,interior of DESI Training Center ©Naquib Hossain

_________

泥土与纺织

Mud and Textiles

“泥土是唯一一种可以在环保方面达到闭环的建筑材料。它取自大地归于大地,重复利用也不会对质量造成任何损失。”

“I think earth is the only material that has a closed loop in terms of sustainability. You can take from the ground and recycle without any loss of quality.”

1.

采用土制建造工艺也使得您可以让很多村民可以参与进来,就算他们不是技术工人也可以。您如何控制土制建筑的施工质量?

Earth construction allows you to engage the villagers who are not trained construction workers because it doesn’t require skilled laborers. How would you control the quality of earth construction?

土制建筑同样可以施工精准,主要是看施工工艺,这和别的材料没有任何不同。但是你不能逆着材料的特性设计建筑,不能非要用土制结构在湿润多雨的地区造一个像MAXXI美术馆一样的建筑。充分掌握好材料特性、结合建筑所在环境特点,就可以建造出精准、长久的建筑。中国的土楼就是很好的例子。

我们一般认为是永久性的建筑材料也并不意味着永恒,就比如说混凝土。往往会在几十年后就显得又丑又不健康。这时候我们又不能便捷地剖开混凝土,看看它里面究竟使用的是什么样的钢筋,哪种泥沙,要怎么去修复。但是土这个建筑材料不一样,泥墙裂了缝,我们只需要灌点水和上泥浆就能完成修补。

土制建筑可以在任何一个气候区屹立数百年。对于土制建筑,我们的认知盲点不是在技术方面,而是在于理念。比如Martin Rauch的预制工艺(pre-fabrication)可以高效高质量地将土制结构运用在大尺度的建筑上。你可以用高科技的方式做土制建筑,也可以用低技术的方式去做。这是土制建筑的优势,也正是我相信土制建筑可以用在大型建筑上的原因。另外,这种材料遍地都是,而且成本低廉。

You can definitely do earth construction in very accurate ways. It’s about the quality of the craftsmanship. You can do quality control just as in any other materials. But what you cannot do is create an architecture that doesn’t fit the nature of the material. You cannot build a MAXXI Museum out of mud in a rainy area. You have to understand the parameters of the site, then with your design, within that framework, you can create a precise, long-lasting building, just like Tulou in China.

The buildings we perceive as long-lasting are not built for eternity. Concrete buildings look ugly and unhealthy after a few decades. Meanwhile, there is no easy way to fix the concrete. We cannot open the concrete and check what’s going on with the steel rebar inside the concrete, what type of sand is used, etc. In contrast, in the village, if there’s a crack in the mud house, we put some water in and fix the crack.

The earth construction can stand for several hundreds of years in every climate zone. We have the know-how, but we are missing a narrative. With pre-fabrication that Martin Rauch is doing, you can scale them up in a fast and controlled way. You can do the earth construction in a high-tech way as well as a low-tech way. This is why I believe in scaling up earth construction is possible. Also, the material is readily available and not costly.

▼《土制建筑》

Anna Heringer, Martin Rauch和Lindsay Blair Howe联合创作

Book on Earth Construction co-authored by Anna Heringer, Martin Rauch and Lindsay Blair Howe

2.

您的设计不止于建筑,在别的手工艺上也有所涉猎,就比如比如织物设计。能否介绍一下您对织物设计的兴趣的起源,以及现在在进行的项目?

Your practice goes beyond architecture and focuses on different crafts, including textiles. Can you tell us about how you became interested in textiles and the projects that you are working on?

在孟加拉做了22年的项目,我没有办法对这里的纺织物熟视无睹,以及它对这里人的迁移的影响。很多村庄里的妇女去到达卡的工厂里做工。外出打工的,有给自己攒嫁妆的年轻姑娘,也有带着孩子的母亲们。这带来了一系列的后果。她们的家庭生活被撕裂,同时又在不人道的环境下工作。在搬离村庄去到城市的同时,失去了村庄里的人际交往和人脉资源。比方说,在村庄里,有土地就可以种庄稼养活自己,有竹子和泥土就能搭一个屋子,村民会互相帮忙,生存成本几乎为零。然而在城市里需要租房,没有与邻里的社交,一周至少有六天工作十小时以上。陪伴和抚养孩子也是个大问题。白天孩子们只能一起呆在房间里,不像在村庄里遍地都是他们的游乐场。

为什么她们要离开村庄去城里打工?在收成不佳的小年里,村里人需要找别的经济来源。而纺织工人是当地社会唯一接受的适合女性的职业。因此很多家里的姑娘和母亲到自动化的服装厂打工。自动化生产的服装产业有它的弊端,重数量而轻质量。我看到新闻说德国平均每人每年购买六十件衣服,还不包括内衣和袜子,每把椅子上放上一件的话足够铺满两间教室。如果我们少买几件,多用几年,会是更可持续的一种方式,也可以给生产织物的人更合适的报酬。

After 22 years of being in Bangladesh, you cannot look away from the garments that help so much in shaping the way that people have settled. Many women are leaving the villages to work in textile factories in Dhaka [the nearest city]. Some are girls saving for their dowry, some are mothers with children. This has a series of consequences. It’s tearing families apart. The women are forced to live in inhumane conditions in the city, and they completely lose the social network they have in the villages. For example, as a family in the rural area, you can build your home out of the earth and bamboo, you can plant your own food– you don’t have to pay for living. In cities, you would have to rent a place. You would hardly have any social life with the neighbors because the women have to work at least 10 hours a day and 6 days a week. Then, childcare becomes a problem too. The kids are mostly locked indoors the entire day with no space to be outside. In the villages, the kids have plenty of playgrounds, as there is hardly any traffic.

Why do the women leave the villages to work in the factories? In the rural areas, if there’s a low season for agriculture, the families don’t have any source of income. To work in a textile factory is the only professional choice the women can make. That’s why textile factories are shaping a lot of settlement. The automatized process of the fashion industry is problematic. It values efficiency more than quality. I just saw the news that in Germany, one person purchases 60 pieces of clothes per year on average, not including underwear and socks. Just imagine two school classrooms filled with a piece of clothing on every chair. It would be a more sustainable way of living if we purchase clothes that last longer and buy fewer pieces. At the same time, we can pay much fairer prices to those who make the clothes.

“作为消费者的我们,很少会意识到我们的生活消费方式在影响着地域空间的变化。”

“As consumers, we are not aware that our way of living is also shaping spaces .”

作为消费者的我们,很少会意识到我们的生活消费方式在影响着地域空间的变化。 如果我购买工厂里生产的衣服,意味着我在鼓励集中式的机械生产模式和不人道的工作环境。如果我买一件受公平贸易保护的产品,那我在为保护村庄里的安宁生活尽绵薄之力。我们所买所用,皆与空间挂钩。

因此,与其将农村人从他们熟悉的生活环境中抽离,迁移到城里,不如把工作机会引入到农村。这就是我在努力做的。我希望妇女们可以留在她们生活的环境,建立自己的家园。我和非营利组织Dipshikha以及来自我的家乡的织物设计师Veronika Lena Lang一起合作这个项目,设计的织物可以完全用去中心化的生产方式,不需要电力,不受流行时尚周期的影响。

As consumers, we are not aware that our way of living is also shaping spaces . If I buy a piece of clothing here, which is made in Bangladesh, I am encouraging the centralized factories and the inhumane environment to the women workers. If I am buying a fair-produced product, then I support a good place in the village. There are spaces attached to our clothes and the goods we are using.

That’s why it is important to bring work to where the people are, in rural areas, instead of drawing people from rural areas into the few hubs out of their living context. What I’m trying to do is to bring work to the rural areas where the women can stay and create their own habitat for themselves. I do this with the help of NGO Dipshikha and the tailoring masters from my hometown, Veronika Lena Lang, to design products that can be produced in completely decentralized ways – without electricity and without following any fashion cycles.

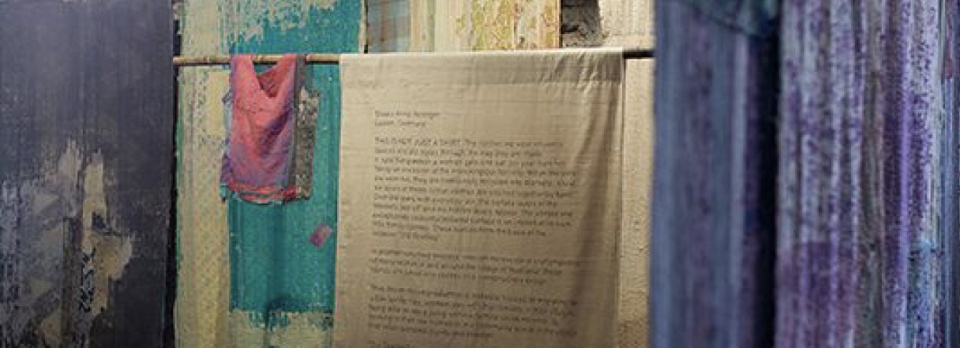

▼孟加拉的纺织品,textiles in Bangladesh ©Studio Anna Heringer

当我们说起孟加拉生产的衣服,想到的都是很基本的布料款式。其实孟加拉向来都有非常精美的传统织物,比如平纹细布(muslin cotton)、丝绸,只是我们没有充分发挥出他们的潜力。就像建筑师分析项目基地的潜能一样去分析传统织物并从中创造出新的设计。

我设计中运用的织物本来就是独一无二的。回收的纱丽,永远不会被任何自动化的生产取代。在村庄里其实可以产出更高质量的织物。对于孟加拉、中国这样有自己的纺织文化的国家来说,要保护好自己的文化积淀何其重要,以避免不被激光打印之类的新科技替代。我认为我们的再利用的纱丽设计出的产品独有的特质是不会被任何机器制品取代的。

When we think of Bangladesh, we normally think of the clothing with very basic prints. However, Bangladesh has always been known for its fantastic traditional textiles, the beautiful muslin cotton and the silk clothes. It is our problem that we did not unleash the full potential of the textile in Bangladesh. Just as architects look at what the real potential of a place might be, I do the same to look at what textile traditions are there in order to create a fashion/product from that tradition.

The materials I use for Dipdii Textiles are already unique: they are recycled saris. They are so unique that they can never be taken over by some automated processes. For countries with rich textile traditions, it’s important to protect the traditional crafts so they are not completely replaced by the new “press-the-button” manufacturing technologies, such as laser cutting. I think recycled saris are a material product that won’t be replaced by any machine production.

▼回收的纱丽,recycled saris ©Dipdii Textiles

▼2018威尼斯双年展上的展品:这不是一件汗衫,而是一个游乐场

“This is not a shirt. This is a playground” – project for 2018 Venice Biennale ©Julien Lanoo

3.

您成立了Dipdii Textiles工作室,作为有别于纺织工厂的另一种织物制作的模式。是否可以描述一下您的织物工作室的工作环境?

You established Dipdii Textiles as an alternative paradigm to textiles production factories. Can you describe the working environment of the Dipdii Textiles workshop?

起初我们在户外干活,大家可以把织物带回家工作。我们想这样分散在家干活是最好的,因为她们可以灵活安排工作的时间,比如等孩子们睡着以后。后来我们发现大家其实很享受这段暂时离开家庭,聚在一起工作的时光。我自己能体会这个心情,虽然家庭时光很美好,但是也需要有和出去和别人打交道的时间来平衡。另外也因为她们经常一边干着针线活一边聊天,分享生活中的点滴,互相支持。

In the beginning, we were using the existing structures and the women were working outdoors. We said that everyone could take the textiles and work at home. We thought this decentralized way of working would be the best thing for women, as they could choose when to do the work, for example, when the children are asleep. Then we figured out that the women enjoyed working together and to have a chance to break out of their homes. I can relate to this feeling. The family is fantastic but sometimes you also need balance to be outside and meet other people. Also, while the women are stitching, they chat about their life and support each other all the time.

▼Dipdii Textiles一起工作的场景,women working together at Dipdii Textiles ©Stefano Mori

因此我们建了一个美丽的建筑,楼下是残疾人活动空间,楼上是工作室。这是一个灵动的建筑,跟METI学校的直白与棱角很不同。建METI的时候是要证明泥土也可以有精准的建造工艺,到了这个工作室的时候,我就可以自由地发挥泥土的可塑性了。与此同时,我也想传达一个信息:我们不都是一个模子刻出来的,人类的美在于每个人的不同。我想在设计中传达建筑的包容性,因此建筑外立面上就能看到舞动的坡道。这种传递信息的能力,是建筑蕴含的力量。

And now they also have a really beautiful workshop building called “Anandaloy”. There’s space for people with disabilities on the ground floor, and the workshop is on the top floor. It’s a dancing structure, in contrast to METI school, which has straight profiles with hard edges. In the beginning, it was important to show that we could build a rigid structure with mud. Then with this building, I wanted to use the plastic capacity of mud. Also, I want to show that, as humans, we are not all the same. I want to celebrate the fact that we have members of our society who do not fit in the typical box. There’s beauty in this diversity. For this building, you can see a ramp dancing around the classroom from outside the building. As the only ramp in the village, it triggers the discussion about inclusiveness. Transmitting messages is an important power embedded in architecture.

▼Anandaloy,发挥泥土的可塑性,Anandaloy showing the plastic capacity of mud ©Kurt Hoerbst

▼Anandaloy建造过程,Anandaloy in construction ©Stefano Mori

4.

您许多年来都是一边做着织物设计,一边进行着建筑设计。在这两个不同的领域穿梭,是否给您带来了与众不同的设计视角?

You also have quite a lot of other textile projects going on while you are running your architecture studio. How does moving through different worlds impact the way you see things?

现在我的大脑平分给了建筑和织物,但这两件事不是完全割裂的。去年我带领哈佛建筑设计学院的学生去孟加拉的难民营,给那里的孩子们设计建筑,今年我联系了难民营里的妇女们,和Rudrapur村子里的人一起合作织物。图案是孩子们画的他们的记忆中的家园,拿到村子里定好布上的构图,之后带去难民营,和妇女们一起参与缝制。

My brain space is divided into half with architecture and textiles now, but they are not completely separated. Last year I taught a studio at GSD (Harvard Graduate School of Design) and brought the students to Kutupalong refugee camp in Bangladesh. This year I’m connecting the women in the refugee camp to collaborate with the women in our (textile) workshop in the village of Rudrapur in Bangladesh. We asked the children in the camp to draw their memory of home during the studio trip. Now we are putting these images on textiles. The women in the village compose the drawings onto blankets. Then we bring the blankets back to the refugee camp and the women in the camp work on them together.

▼与Kutupalong难民营的妇女一起完成的纺织品项目,a textile project in collaboration with women at Kutupalong Refugee Camp ©Shaowen Zhang

_____________

建筑师的社会责任

Social Responsibility of Architects

“对建造的热情是写在人类的基因里的。如果我们能把个人都聚集在一起,就能建立强大的社会纽带。”

“It’s in our DNA that every person wants to build something. The process is not about one man’s work. It’s about coming together and that helps build up relationships.”

1.

在DESI Training Center项目,参与到建筑的建造过程对村子里的女性有什么影响?

In DESI Training Center, how did participating in the building process impact the women?

参与建造的过程给妇女们带来了自信。一般来说,孟加拉的女人们从来不会出门闲逛,或者在茶馆聊天,但是这次我们一起去了茶馆。一开始她们觉得不太自在,但是后来就习惯了,她们就和男人们一样在茶馆会朋友。另一方面,她们和男人们挣一样的钱,因此在当地社会中的地位也得到了认可。

类似的事情也发生在跟我一起做织物项目的团队上。在一个印度教的节庆期间,有个活动是村里的小伙子和男人们在几百人面前跳舞。姑娘们过了十二三岁就不应当再和大家一起跳舞了。但是我当时能看出来姑娘们还是很想跳舞。她们在没有人的时候,会在我们的工作室附近自己跳。但是她们绝对不会在舞台上跳舞,尤其是我们的团队里还有寡妇,在当地的文化里,寡妇的生活是不应该有欢乐的。于是,我跟她们说我很想跳舞,我也知道她们也跟我一样。“要不我们作为一个团体一起跳舞吧!”我们就加入了跳舞的队伍。一开始她们会有些害羞,但最后她们都完全放开了包袱,大家也都为她们喝彩。能感觉到,她们的公共参与度比以前提高了很多。

The women became more confident after the construction process. They usually never go out and hang out at the tea stores. But we all went there together. In the beginning, they were not very comfortable. They were not sure if it was okay for them to be at the tea store. After a while, it became normal and they did it just like the men. Because they were earning the same money as the men and, of course, they had a public presence in society.

I have another story with the women that I worked with for the textile projects: During the Hindu festival, there’s an occasion when the boys and the men in the village are dancing in front of hundreds of people. However, for girls, it’s not appropriate to be on the stage after the age of 12 or 13. I felt that the women would love to dance. They were dancing when no one was watching in our workshop area, but there was no way to go dancing in the public as a woman, especially when there were some widows amongst us. Widows were not supposed to have any fun in life. So, I said, “We all go as a group and we dance,” and we went dancing. They were extremely shy in the beginning. But in the end, they completely enjoyed themselves and everyone was cheering them up. They became more confident and they felt that it was okay to be part of public life.

2.

您谈到DESI Training Center时提到了建筑的建造过程改善了村里的家庭关系和社群关系。您如何看待过程的力量?

When talking about DESI Training Center, you brought up that the process of the building construction improved the relationships in the families and in the community. How do you interpret the power of the process?

我们整个社会都缺乏对过程所蕴含的力量的认知。我们应该学习如何运用这种力量。社会中的种种分歧,甚至贫富差距、政党纠葛,其中有部分原因是因为我们缺少共同参与的项目。古时有整个社区一起建造教堂、塔寺、学校或是市政楼的传统。当大家聚在一起,不是七嘴八舌争论各自的观点,而是一起分担体力活、一齐把绳子往一个方向拉的时候,自然就团结了起来。这是我们今天遗失了的东西。有句话说得很好:如果你想播撒仇恨,就往人群中撒一把米;如果你想团结人们,就让大家一起建造一座高塔。 大家对共同建造的产物感到自豪,这是大家共同的成就,这个团体共有的标记。大家会对自己的潜力能创造出什么更有自信,对整个社区也更有信心。

这个元素我和Martin Rauch也运用到了St.Peter of Worms教堂的项目里。社区里当然会有不和的情况,因此你要采取一些行动来让大家团结协作起来。我们聚集了社区里的人,一同用土夯出祭坛。我观察到最终人们一起夯土、共同努力,就像孟加拉村庄里的人们一样。这让我感到鼓舞,也从中学到了很多。从德国到孟加拉,过程的力量都是共通的。我们建筑师们需要学会运用这种力量。对建造的热情是写在人类的基因里的。人们之所以会涌入宜家、家得宝之类的卖场去挑选这把椅子、那个帘子,自己拼装,正是因为每个人都想自己建造自己的家。如果我们能把个人都聚集在一起,就能建立强大的社会纽带。

The power of the process is something that is undervalued in our society. We need to learn how to use it. In our society, the relationships between people are not strong enough: we have political issues, the gap between parties, and the gap between the rich and the poor. This is partially caused by the fact that we do not have enough common projects together. In the past, it was part of the tradition for a community to come together to build a temple, a church, a mosque, a school, a mayer’s house. There were also traditions that you help build each other’s house. In the village, these traditions brought people together. Instead of discussing with each other about the different opinions, you could bring everyone together physically and ask people to make an effort to build something together. Then, everyone would pull in the same direction. This is something that is lost today. There is a great saying: “If you want to bring war or hate, just throw rice amongst people. If you want to unite them, get them to build a tower together.” Because when people build something together, they would be proud of the structure, and they would have something to hold on to as their identity and pride. This builds confidence not only in people’s own potential, but also in the community.

This is an element we also used for the project I did together with Martin Rauch in the cathedral St. Peter of Worms in Germany. The community came together to create an altar, rammed out of earth. Observing the community was inspiring to me. Of course, people in the community also fight against each other sometimes, and you have to make an effort to stop the fights and build a team. However, in the end, everyone rammed the earth together and united to finish the altar. The power of the process worked as well in Germany as much as it did in Bangladesh. As architects, we need to learn to use this power. It’s in our DNA that every person wants to build something. We all want to build our own home, that’s why we rush into IKEA and Home Depot to buy this chair and that curtain, and assemble them by ourselves. The process is not about one man’s work. It’s about coming together and that helps build up relationships.

▼社区居民参与夯土祭坛的建造

people in the community participated in the construction process of the altar ©Norbert Rau

▼Wormser Dom中的祭坛

Wormser Dom’s altar interior ©Norbert Rau

3.

您的价值观是什么?

How would you describe your value system?

我想就是把幸福最大化。每个人一辈子都在追求被别人需要,我一生也在努力发挥我在建筑方面的才能。我希望尽可能地聚集更多的人和更多的才华,到最后我们站在一起建成的建筑物前,感受着成为它的一部分,看着共同努力的结果,洋溢着对自我价值的肯定以及对手上的材料和资源的信赖。

I want to say it’s about global happiness. To feel needed is something that’s part of everyone’s life goal. To be able to live according to the talents you have, this is what I’m trying to do with my architecture. I include as many people and as many talents as possible. In the end, we all stand in front of the building and feel that we are part of it. We are filled with confidence and trust in ourselves, in the team, and also in the materials and resources that we have.

4.

您是怎么理解“客户”的?

What is your understanding of “a client”?

简单来说,客户是想造房子的人。就我而言,我每到一个地方都会注意到当地的人的生活中有什么需求。我会去想能找到什么资源来启动一个项目。当看到一个挑战,定义了问题,并且知道你有能力去做些什么的时候,就很难什么都不做。 就像织物的项目一样,那么精妙的传统布料没能物尽其用,我想做点什么来发挥出它的潜质,因为我觉得我能为它出一份力。

我的项目并没有甲方。不少建筑师把很多时间花在做竞赛上,我把这些精力用在启动自己的项目上。起初是通过众筹之类的方式,后来开始有公益组织带着资金找到我做项目。比如有教堂请我以人文的、环保的方式设计建筑,想以此证明其可行性。虽然没有一个特定的甲方,但幸好我有一群有远见并且和我想法一致的客户支持着我。即便这样,这种非常规的项目还是有很多困难,尤其在条条框框很多的德国。

A client is someone who wants to build something. This is a simple definition. Based on my personal experience, when I go to a place, I would notice that the people are in need of something. I’ll find what resources can be gathered together to initiate a project. When you define a problem and a challenge and have a feeling that you can do something, it’s hard not to do it. As with the Dipdii Textiles, I saw the fantastic potential, which no one is using, so I started using it because I thought I could.

I don’t have a client. A lot of architects invest time doing competitions. Instead of doing this, I invest time in initiating my own projects. In the beginning, I did crowdfunding. Now people and organizations start to approach me with a building budget set up. Organizations that are supposed to work ethically, like the church, want to have a building made in a way that’s ethically and environmentally-sound to prove that’s possible. I don’t have a “client”, but luckily, I have visionary people who support me and share the same goal with me. It’s not always easy because we are not doing projects in a standardized way, or designing with conventional materials, especially in Germany with all the regulations.

“与前几十年不同,现在新一代的建筑师们非常迫切的在把建筑中的美学和意义结合起来 。”

“The younger generation is hungry to combine the aesthetic part and the meaningful part of architecture.”

5.

您怎样看待建筑师在当今社会中的角色?

Do you see the role of architects changing in today’s society?

与前几十年不同,现在新一代的建筑师们非常迫切的在把建筑中的美学和意义结合起来。挑战是在于建筑施工的盈利链条:势必常规的、标准化的设计是最省时省力省钱的,同时经济收益最大。就这一点来说,我们这个行业在思想上需要调整。

气候变暖给我们敲响了警钟。我相信不久我们就要面临征收碳税相关的问题了。目前主流的建筑材料并不是可持续的。钢材价格在上升,混凝土面临全球性砂砾短缺,环境危机会比我们想象得来得更快,要求我们彻底调整设计方向。高科技并不能解决所有问题,我们也不能简单地指望未来可以在脑中构思交由3D打印机打出整幢建筑。

The younger generation is hungry to combine the aesthetic part and the meaningful part of architecture . That wasn’t the case for the last few decades. But the challenge is that there is so much money associated with construction and you can make much more money if you do things in the standard and conventional way. I think we need some shaping up of our profession.

The wake-up call is coming with climate change. I’m sure we will have issues with carbon tax soon. The mainstream building materials are not always sustainable. Steel is getting more expensive. Regarding concrete, we are running out of the sand. The issues are coming faster than our expectations. Then, we have to change our way of creating architecture completely. New technology will not always solve all the problems. We cannot simply have a fantasy building on our screens or in our minds, send it to a 3D printer and glue the print outs.

“我们的创造力就体现在如何让古老的自然材料焕发新的光辉。”

“I think it is our core capacity as designers, to use our creativity and technology to use the old materials in a modern way.”

我们需要回归到最基本的东西。正是这些东西创造出了世界上所有绮丽的建筑文化,那些我们心之所向的度假地。这些脱胎于质朴智慧的建筑格外真切。当我们的设计依靠本土特性和资源的时候,就能站得更稳、走得更远。你也许会觉得古老的材料和现代社会格格不入,但是我们设计师的特长不就是创造力吗?我们的创造力就体现在如何让古老的自然材料焕发新的光辉。

当然本土材料有它的弱点,一般对所在环境的气候有所限制,但是如果我们能把这个限制和弱点作为设计的契机,就可以因地制宜地创造出朴实真诚的建筑。就地取材另一个优点是可以发挥当地的建筑工艺,用当地社区的手艺人参与施工,而不是高技术工人。如果建筑师能有创造性地利用好这些资源,就可以做出超越贴着明星标签的世界建筑。

We have to go back to the basics which have created all the beautiful building cultures all around the world, where we all want to go and spend vacations. These places based on basic wisdom are so authentic. You are standing on much more stable feet if you rely on the resources that are locally and naturally available. We sometimes have a hard time imagining how the old materials can fit in our contemporary world. But I think it is our core capacity as designers, to use our creativity and technology to use the old materials in a modern way.

Of course, the natural materials are always vulnerable to the local climate. But if we take this vulnerability and specificity of the local materials, we can create authentic architecture that is perfectly tailored to that place – architecture that is radiating the beauty and identity of the locals. It would be easier to involve local craftsmen instead of skilled labor. If architects can utilize these resources in a creative way, we can create something that’s beyond the branded, globalized architecture.

▼METI学校内部,用本土材料创造质朴真诚的建筑空间,interior of METI School, architecture with authenticity ©Peter Bauerndick

More: Studio Anna Heringer,更多关于他们:Studio Anna Heringer on gooood.